by Tom Waters

|

| 'Abuzz With Charm' (Coleman, 2013) |

Standard dwarf bearded irises (SDBs) are defined as bearded irises between 20 cm (8 inches) and 41 cm (16 inches) in height. But behind that simple definition is an exciting story of the creation and development of a family of wonderful garden plants unknown in nature, beginning with two curious hybridizers collaborating on an experiment and culminating in what would become an enormously successful class of irises, second in popularity only to the tall beardeds.

The story begins in the 1930s with Robert Schreiner seeking out seeds of the dwarf bearded species

Iris pumila, native to eastern Europe. There were already dwarf irises grown in gardens at that time, nearly all of them derived from

Iris lutescens, a species native to the western Mediterranean: Italy and southern France. There was not much potential in breeding these dwarfs, however. The color range was limited (yellow, violet, and occasionally off-white), and attempts to add more variety by crossing them with tall bearded irises produced only sterile intermediates, a dead end as far as improving the dwarfs was concerned.

|

| Iris pumila |

Iris pumila offered the prospect of something new for dwarf breeding. Although not grown in western Europe or North America, it was known to iris specialists. It was one of the iris species originally listed by Linnaeus, and was described in W. R. Dykes's

The Genus Iris and other sources. It is a truly diminutive iris, virtually stemless, with the tip of the blooms often only 10 or 15 cm above the ground. Its range of colors is delightful: yellow, cream, pure white, violet, purple, and blue, almost always with a darker spot on the falls. Instead of just lamenting its unavailability from commercial sources, Schreiner initiated communication with plant enthusiasts in eastern Europe, and was eventually able to import some seeds of this promising species.

By the 1940s,

Iris pumila was being grown by a small handful of iris hybridizers in the USA. Two of them, Paul Cook in Indiana and Geddes Douglas in Tennessee, decided to exchange pollen.

Iris pumila was blooming in Indiana around the same time as the tall beardeds were blooming in Tennessee. The results of these crosses delighted them both. The stems grew about 30 cm in height, only slightly larger than the garden dwarfs of the time. There were two buds at the top of the stem, and often a third on a short branch. The flower form was perky and modern by the standards of the time, and the colors were bright and varied wonderfully. And, most extraordinarily, these new hybrids were fully fertile and could be bred with one another for as many generations as the hybridizer desired. These were the first of a new type of iris, now called SDBs. Paul Cook introduced the first three to the world in 1951: the clear yellow

'Baria', blue

'Fairy Flax', and white and green

'Green Spot', which achieved an enduring popularity among iris enthusiasts.

|

'Green Spot' (Cook, 1951)

photo: Barbara-Jean Jackson |

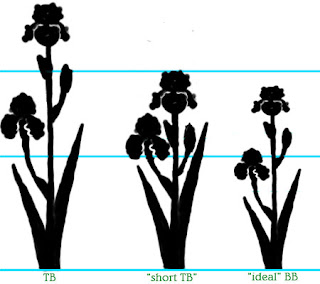

The creation of these new hybrids soon caused controversy. Were they dwarfs or were they intermediates? Many dwarf enthusiasts insisted on the latter view.

Iris pumila was a dwarf, after all, and crossing dwarfs with TBs was the classic recipe for intermediates. Furthermore, they argued, no true dwarf iris could have a branched stalk, which SDBs often did. Others, however, noticed that these new irises were much closer in size and general appearance to the dwarfs than to the intermediates, and preferred to just stretch the definition of "dwarf" a little bit to accommodate the new hybrids. Geddes Douglas thought they should be in a class by themselves, neither dwarf nor intermediate, and proposed calling them "lilliputs".

By the mid-1950s, those who preferred grouping the new irises with the dwarfs had prevailed. The AIS adopted a classification where any bearded iris up to 16 inches in height was considered a dwarf. The Dwarf Iris Society refused to accept this however, and the result was a schism between the two groups, with the DIS having its own judging standards and its own system of awards. This state of affairs was untenable, and by 1958, it was clear that the classification problem needed serious rethinking.

|

| 'Rain Dance' (B. Jones, 1979) |

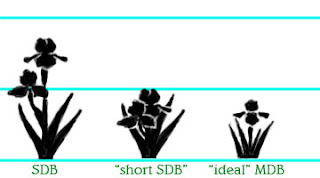

The final outcome was abandoning the simple division of dwarf, intermediate, and tall, and replacing it with four "median" classes in between the dwarfs and the talls. The intermediate class remained, but now there would also be a new class for "lilliputs" and two more classes in the intermediate height range, one for small TBs (border bearded) and one for the dainty diploid "table irises" (miniature tall bearded).

So the new

pumila/TB hybrids now had their own class, but what should they be called? Douglas's name "lilliput" was deemed a bit too fanciful. The final decision was to call them "standard dwarf bearded" and refer to the smaller true dwarfs as "miniature dwarf bearded". The Dwarf Iris Society would continue to promote only the MDBs, while a new organization, the Median Iris Society, was created to promote the four median classes: SDB, IB, MTB, and BB. The result is a slightly perplexing situation where the SDBs, although having the word "dwarf" as part of their name, are technically medians, not dwarfs.

This brand new type of iris shook up the conventional thinking of the time, but the result was much better than if they had been forced into either the dwarf or intermediate categories. Having their own class and their own awards gave great encouragement to breeders striving to improve them. And the improvements came rapidly. Breeders like Bee Warburton and Bennett Jones were at work from the beginning, scarcely behind Cook and Douglas in producing new SDBs. Before long, most hybridizers were no longer crossing

Iris pumila with TBs to produce new SDBs. It was easier to simply cross the existing SDBs with each other, and the results were usually better too.

The influence of the SDBs extended beyond their own class. Today, most IBs come from crossing SDBs with TBs, and most MDBs derive from SDBs as well.

SDB breeding produced some extraordinary surprises. It was originally thought that some of the recessive colors and patterns, such as pink and plicata, could only appear in TBs. But it did not take long before they began showing up in SDBs as well. Today's SDBs have virtually all the colors and patterns seen in TBs, as well as the "spot pattern" inherited from

Iris pumila. I think it is fair to say they are the most varied class of irises in existence.

|

'Chubby Cheeks' (Black, 1985)

photo: Mid-America Garden |

In the nearly 65 years since the first SDBs were introduced, there has been a steady improvement in form and substance. Bennett Jones's creamy white

'Cotton Blossom' was hailed as an early improvement in form, with wide round petals and light ruffling. But the greatest breakthrough was Paul Black's

'Chubby Cheeks' in 1985. A prodigious parent for decades, this iris and its descendants set a new standard of form for the entire class.

SDBs are deservedly popular, and not only for their varied colors and appealing flower form. They bloom about a month earlier than TBs in most climates, greatly extending the iris season. Furthermore, their size makes them more versatile in garden design than their larger cousins. They can be tucked in next to a doorway, along a path, or even used in small "postage stamp" backyards where TBs would be out of scale. It's hard to imagine the iris world without them.

And we owe their very existence too a few creative souls whose curiosity prompted them to step outside the status quo and try something different. Who can say where the next great iris success story will come from?