by Tom Waters

There is no excellent beauty that hath not some strangeness in the proportion.

—Francis Bacon

It seems like devotees of the dwarf and median irises, myself

included, are always talking about proportion. All the parts of the stalk, we

are told, must be in proportion: the height and width of the flowers, the

height and thickness of the stalk, even the leaves. Indeed, the American Iris

Society’s Handbook for Judges and Show Officials gives measurements and

ratios to define proper proportion for each class.

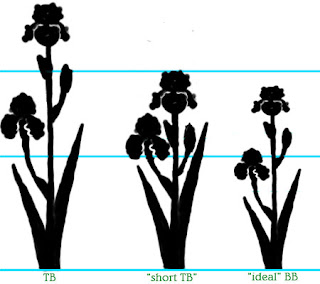

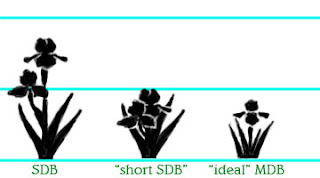

I’d like to raise a philosophical issue about proportion, and how it relates to two iris classes in particular, the border bearded (BB) and miniature dwarf bearded (MDB). These two classes face a similar problem: most BBs are produced by crossing tall beardeds (TBs), and most MDBs are produced by crossing standard dwarf beardeds (SDBs). Since the genetic background of these classes comes mostly from a different, taller class, it is not unusual to find flowers that are large, even when the height of the stem is short. Purists are very bothered by this situation, but short irises with large flowers seem to be popular with iris lovers and even judges. Are the many people who enjoy large-flowered BBs and MDBs just wrong? Should they know better?

The philosophical issue is this: is “good proportion” objective? Is there some numerical ratio of stem, flower, and foliage that is aesthetically optimal? Or is it just in the eye of the beholder? If it is just a personal, subjective preference, then the admonitions in the Judges' Handbook start to seem a bit arrogant and elitist. The classic example of a subjective judgment becoming judging gospel is the case of haft marks. In the mid-20th century, haft markings were the “fault” that everyone seemed obsessed with in TB irises. Yet, what if I think haft marks are interesting or pretty? Is this any different than preferring yellow to blue, or preferring plicatas to selfs? The condemnation of haft marks reflects the struggles of hybridizers. In those early years, it was very difficult to breed a true, clean, self-colored iris. Haft marks seemed to always turn up and distract from the desired purity. So the frustration felt by hybridizers was transformed into an esthetic standard that was promoted as something objective and universal. Once clean selfs were achieved, then people could start to enjoy haft marks for being “something different”!

Many, many “rules” that are enshrined in the Judges' Handbook are relics of the personal goals and frustrations of earlier

generations of hybridizers, even though they are presented as objective aesthetic truths. I think proportion is one of those things. I say this despite

the fact that I, personally, dislike large-flowered BBs and MDBs. If a BB blooms

in my garden with TB-sized blooms and thick, coarse stalks, it does not stay

here another year, no matter how pretty the color or form. However, in all

honesty, I have to describe this as a personal preference.

|

| Allium karataviense |

If there were some objective, universally valid, proportion of bloom to stalk that looks best to everyone, then we would expect it to apply to all kinds of plants. But in fact, we enjoy flowers with all different ratios of bloom size to stem height, without thinking twice about it. Consider two alliums I grow: A. karataviense produces enormous globular flower heads right at ground level. I enjoy it immensely. A. caeruleum produces small, airy blue flower heads on tall slender stalks. I enjoy it also. These two could not be more different. And neither has the proportion of a “good” bearded iris. In fact, I think an iris proportioned like either of the alliums would inspire revulsion in a typical iris judge.

|

| Allium caeruleum |

No, that is not the approach I favor, although I think the

argument should be made from time to time to provoke thought and debate. I

believe there is a good reason for harping on proportion in the dwarf and

median irises, but I don’t think it has anything to do with some objective,

universal standard of beauty.

|

| 'Solar Sunrise' (Black, 2019), a BB whose proportion I like. |

What then? If small-flowered BBs and MDBs are not objectively superior to large-flowered ones, why should we care at all? I think the answer lies in something else: class identity. Consider this: although they fall in the same height range, miniature tall bearded (MTBs) are “supposed” to have smaller flowers and more slender stems than BBs. If one proportion is more attractive, shouldn’t all classes aspire to that same proportion?

To most median aficionados, the answer is obvious: each

class has its own aesthetic ideal. We like the fact that BBs look different from

MTBs. They are like two different styles of music. In our minds, we may have a

picture of the ideal, the prototype, as it were, for each class. It is these

mental prototypes that give each class its identity, its center of gravity in

the great sea of diversity that hybridizers have produced for us.

So I think what we are complaining about when we complain about

out-of-proportion BBs or MDBs is the erosion of the identity of the class, the weakening

of the mental prototype. The reason I have singled out BBs and MDBs is that the

irises in these classes are mostly “spill-overs” from TBs and SDBs, respectively.

There is a relentless pull on these classes to merge together with the larger

classes that give rise to them. If a BB is just a TB that is short, why not

call it a TB?

| 'Icon' (Keppel, 2008) an MDB whose proportion I like. |

Some have sought to strengthen the identity of these classes through breeding. Lynn Markham’s BBs

were produced intentionally to reinforce the distinct identity of the class. Ben Hager used a similar strategy to reinforce the identity of the MDB class. These were valiant efforts, but they were not sufficient to turn the tide. So many people are crossing TBs that the “accidental” BBs that emerge from TB crosses far outnumber the “intentional” BBs that are produced by the small number of breeders who are interested in the class as an end in itself. Exactly the same is true of the MDB class.

But if nothing else, perhaps we can shift the language of

the conversation a little. Instead of talking about “good” or “bad” proportion,

perhaps we can talk instead of class identity. That seems more accurate and

to the point.