Forty-some years ago, when I was a precocious iris-obsessed

teenager, I convinced my mother that our vacation to California to visit my

sister and her family should become a tour of iris hybridizers’ gardens. So it

happened that I ended up in Ben Hager’s living room, with a huge bouquet of ‘Beverly Sills’ on the coffee table, talking irises while my mom and sister politely enjoyed

the ambience and hospitality.

Hager presented a somewhat intimidating figure, with his

bald head, precise beard, and dry wit. He was also something of an iconoclast.

At an after-dinner speech at the 1980 American Iris Society convention in Tulsa, he basically

dismantled the whole premise of the judges’ training program by asserting that judging

irises was an utterly subjective undertaking; and we should give up our

pretensions of authority and just let people like what they like, which is what

we all do anyway.

As a hybridizer, Hager had few equals, in my estimation. He

worked with all classes of irises, and won high awards wherever he turned his

attention. He created the tetraploid miniature tall bearded (MTB) irises almost single-handedly, by sheer

force of will, it seemed. Furthermore, he had a rare combination of

creative, inspired vision coupled with solid knowledge, dogged persistence, and patience. I rank him along with Sir Michael Foster and Paul Cook as one of

the true ground-breakers in the history of iris development.

Today, I want to talk about one of Hager’s grand projects,

an effort to re-create the miniature dwarf bearded (MDB) class, a work that spanned four decades.

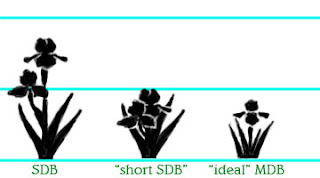

In the 1970s, new MDBs were created by hybridizers combining standard dwarf bearded (SDB) with the species Iris pumila in

various combinations. There were basically three possibilities: pure pumila

breeding, pure SDB breeding, and SDB x pumila crosses.

Hager rejected pure pumila breeding (although he did

introduce one, ‘Ceremony’, in 1986) for two reasons. First, being just a single

species, it lacked the genetic variety needed to get the innovative colors,

patterns, and forms that hybridizers crave. Second, he found its growth habit

(mats covered in bloom, like rock-garden plants) to interfere with the appreciation

of the form of the individual iris bloom.

Hager also rejected the SDB x pumila route, although it was

very popular with other MDB hybridizers of the time. The issue here was poor

fertility. Seedlings from this type of cross show only limited fertility, and

are almost impossible to cross amongst themselves, making line breeding an

impossibility. Hager felt strongly that a class of iris can only be improved

and developed if a fertile family can be established, so that breeding can

continue for many generations without fertility barriers arising. He introduced

no MDBs from this type of breeding.

That left pure SDB breeding as a recipe for creating MDBs.

Hager recognized this as the path of greatest promise, but not without

reservations. This is the type of breeding with the greatest variety of colors

and patterns, and the most adaptable to mild-winter climates. MDB-sized seedlings

do arise from SDB x SDB crosses, but they are the exception (most seedlings

will be SDBs like their parents). Hager wanted a more focused program than just

waiting for these happy accidents. He wanted a line of MDBs that would produce

more MDBs, consistently.

He found his answer in his tetraploid MTB work. The

tetraploid MTBs were derived from crossing tall bearded (TB) and border bearded (BB) with the species I. aphylla, a many branched iris

genetically compatible with TBs, although much smaller. Crossing his tetraploid

MTBs with I. pumila, he reasoned,

would produce irises of the same chromosome type as the SDBs, but presumably

consistently smaller. Furthermore, they would be completely fertile with MDBs

from pure SDB breeding, part of the same fertile family. You may read one of Hager's articles on this plan on the DIS website.

|

| 'Libation' |

|

| 'Gizmo' |

|

| 'Prodigy' |

Hager introduced the first MDB of this type, ‘Prodigy’, in

1973. Its pod parent is a seedling of TB ‘Evening Storm’ (Lafrenz, 1953) X I. aphylla ‘Thisbe’ (Dykes, 1923). The

pollen parent is the I. pumila

cultivar ‘Atomic Blue’ (Welch, 1961). It is thus ¼ TB, ¼ aphylla, and ½ pumila.

Next came ‘Libation’ in 1975. It is a child of ‘Prodigy’

crossed with a seedling of MTB ‘Scale Model’ (Hager, 1966) x I. pumila ‘Brownett’ (Roberts, 1957).

Since ‘Scale Model’ is half TB and half aphylla,

‘Libation’ has the same ancestry breakdown as ‘Prodigy’: ¼ TB, ¼ aphylla, and ½

pumila. ‘Libation’ won the Caparne-Welch Award in 1979.

The third and final of these initial progenitors of Hager’s

MDB line is ‘Gizmo’ (1977), with the same parentage as ‘Libation’.

Hager then set about crossing these (and similar seedlings)

with SDBs and MDBs from pure SDB breeding. As such outcrossing progressed, the

amount of aphylla ancestry decreased and the amount of TB ancestry increased.

The goal was to retain the small size conferred by I. aphylla, but bring in the diverse colors and patterns of the

SDBs. Hager now had a line of seedlings specifically designed to consistently

yield fertile MDBs in each generation.

In all, this project produced 34 MDB introductions. Hager

died in 1999, but Adamgrove garden continued to introduce his MDB seedlings

through 2003. Hager also introduced 19 MDBs from pure SDB breeding, and the

above-mentioned pumila ‘Ceremony’.

Here is a list of all 34, grouped by the amount of aphylla

ancestry present in each.

25% I. aphylla

Prodigy (1973), Libation (1975) Caparne-Welch Award 1979, Gizmo

(1977) Caparne-Welch Medal 1987

Between 12% and 24% I.

aphylla

Grey Pearls (1979), Bluetween (1980), Macumba (1988)

Between 6% and 11% I.

aphylla

Footlights (1980), Bitsy (1991), Cute Tot (1999)

Between 4% and 5% I.

aphylla

Pipit (1993), Jiffy (1995), Self Evident (1997)

3% or less I. aphylla

Three Cherries (1971), although not part of this line, is listed

here for completeness, since it has aphylla in its ancestry from the appearance

of TB ‘Sable’ (Cook, 1938) in its pedigree.

Petty Cash (1980), Hot Foot (1982), Bugsy (1993) Caparne-Welch

Medal 2000, Dainty Morsel (1994), Doozey (1994), Fey (1994), Fragment (1995), Hint

(1995), Chaste (1997), Ivory Buttons (1997), Nestling (1997), Trifle (1997), Simple

Enough (1998), Small Thing (R. 1998), Sweet Tooth (1999), Wee Me (1999), In

Touch (R. 1999), Downsized (2001), Dulcet (2001), Pattycake Baker Man (2001), Behold

Titania (2003), Fair Moon (2003), Gallant Youth (2003), Into the Woods (2003), Pirate's

Apprentice (2003)

|

'Grey Pearls'

photo: El Hutchison |

As far as I can determine, other hybridizers did not take up this

project as Hager had envisioned it, although they did of course use a number of

his irises in their own crosses. My own work with similar crosses has had mixed

results. I cross tetraploid MTBs with pumila each year, but so far have only

bloomed one cross to evaluate, MTB

‘Tic Tac Toe’ (Johnson, 2010) X

I. pumila ‘Wild Whispers’ (Coleman, 2012). The seedlings were all too large for the

MDB class, looking like elongated SDBs or MTBs with deficient bud count. So the

MTB x pumila type of cross is by no means guaranteed to give MDBs in the first

generation.

I do have an interesting MDB seedling from I. aphylla X I. pumila. This

type of cross produced MDB ‘Velvet Toy’ (Dunbar, 1972). My seedling is 5-6

inches in height, and has a distinctive flowering habit. It is branched at the

base like I. aphylla, with both

branches bearing 2 terminal buds each. The four blooms open in succession, at the same height, with no

crowding. It would be nice to see if this trait could be carried on to plants

with a more refined flower. Crossing it with SDB ‘Eye of the Tiger’ (Black, 2008) gave

seedlings that were SDB size or taller, though in a fun variety of color and

pattern. I continue to make crosses with it, mostly selecting smaller MDBs to

pair with it now.

So far, my work with I.reichenbachii X I. pumila seems

the most promising in terms of giving me a consistent MDB line to work with.

Kevin Vaughn has reported good results using Hager’s ‘Self Evident’,

and I have recently acquired this myself, as well as a few others from Hager’s

line.

How should one assess this ambitious program? On some level, it

can surely be deemed a success, as it gave Hager many successful and popular

MDB introductions. Without detailed records from his seedling patch, however,

it is hard to assess how consistent the line was or how much his selection work

over the years contributed to the outcome. Perhaps similar results would have

obtained just by applying the same selection effort to pure SDB lines.

|

'Self Evident'

photo: Jeanette Graham |

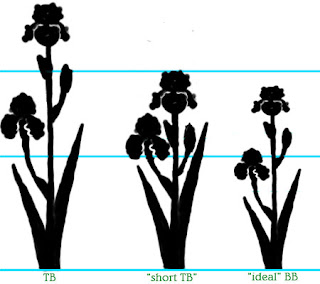

We also have to note that Hager’s tetraploid MTB project is his

most lasting legacy among the bearded irises classes. Tetraploid MTBs are here

to stay, having been taken up by successive generations of hybridizers. The MDB

project did not fare so well, although that may not be any fault of the plants

themselves. Almost all new MDBs today are small selections from pure SDB

breeding, not produced from MDB-specific lines as Hager envisioned. This may

just be a numerical inevitability. There is so much work being done breeding

SDBs that MDBs popping up in SDB seedling patches just can’t help but outnumber

MDBs from the few dedicated lines that hybridizers have worked with. The

situation is reminiscent of that of the BBs, where some good dedicated lines

have been established, but they are still swamped by small selections from TB

crosses, just because so many more TB crosses are made each year.

|

'Bugsy'

photo: El Hutchison |

If you are interested in hybridizing MDBs, I encourage you to heed

Hager’s wisdom and work toward MDB-specific breeding lines, perhaps using

I. aphylla, perhaps carefully selected

from SDB work, or perhaps using other species.

If you are not a hybridizer, but enjoy growing MDBs in your

garden, please seek out and preserve the Hager MDBs discussed in this post.

They are a window onto a fascinating thread of iris history.