by Heather Haley

In this post, I'll continue sharing the story of a growing iris resource on YouTube. The American Iris Society (AIS) uses its YouTube Channel to help organize and disseminate knowledge of the genus Iris, while fostering its preservation, enjoyment, and continued development. Many of the videos available are from the AIS Webinar Series, and their upload was planned for the benefit of all persons interested in irises.

I am very thankful for the AIS Webinar Series, mostly because it has helped me become more involved in this organization. You see, I absolutely love irises and my heart sings whenever I see one. It doesn't matter if the iris is real, digital, or simply decorating an object. This also happens to other members of my family; our love for irises is practically a genetic trait. The only thing I like more than puttering around irises in a garden is spending time with people whose hearts also sing when they see irises. During 2020, few were able to do this in person because coronavirus disrupted many AIS activities for local affiliates, its regions, and the organization as a whole. By July, I was lonely watching iris blooms fade in my garden.

Within days, a most intriguing message appeared in my inbox: the AIS was launching a webinar series! Immediately, my heart was singing a familiar song. For the remainder of 2020, my family and I gathered around an iPad on the kitchen table to enjoy presentations described in Part I of this blog post. Some we caught live, but we also happily watched webinars we had missed as they became available on YouTube.

In 2021, the second year of the coronavirus pandemic, AIS faced another year of uncertainty. With a second national convention in peril, all AIS sections and cooperating societies were invited to give presentations in the webinar series. Most of them accepted, and Part II of this blog post described some of them.

Also in 2021, I received a second intriguing message. This one arrived via text message. It read, "We need help at AIS, and I thought of you." I stood in my driveway a little dumbfounded. Up to this point, I hadn't done much for AIS at the national level, and I questioned what on earth made this person think of me. Sure, I helped my mother with a convention booklet a few years back. I volunteered to compose blog posts about irises. I am also (youthfully?) enthusiastic about all things related to irises. Whatever it was, the organization I credit for my family's love of irises needed help. I was willing and eager to assist.

The following describes the remaining webinars that AIS volunteers prepared, delivered, recorded, and posted to our YouTube Channel during 2021.

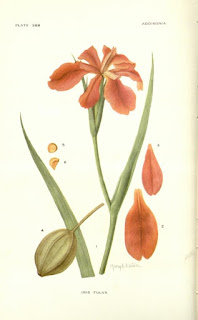

Webinar #15 - “Spuria Irises for Every Garden; a Little History, a Lot of Beauty” with Anna Cadd

Anna Cadd was born and raised in Olesnica, Poland and is the current vice president of the Spuria Iris Society. Although she once aspired to become a medical doctor; her inability to kill rats, frogs and rabbits changed her mind. Her interests turned to botany and led to a Masters degree in Biology and a Doctorate in Plant Ecology. In this webinar Anna shares her enthusiasm for spuria irises with a little history and a lot of beauty.

Convention co-chairmen Howie Dash and Scarlett Ayres previewed the gardens for the 2022 AIS National Convention. They shared a walkthrough of each garden in bloom and interviews with the garden owners. If you are interested in this convention or others, visit the AIS website for more information and hyperlinks.

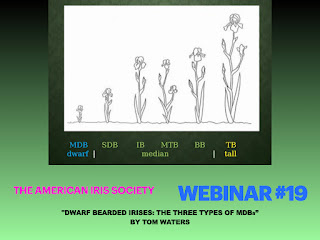

Tom Waters began growing and hybridizing irises in the 1970s. He has served as yearbook editor and president of the Aril Society International, and is currently president of the Dwarf Iris Society. He works as a radiation protection manager at Los Alamos National Laboratory and lives in northern New Mexico with his wife Karen. In this presentation, Tom outlined the origin of the modern miniature dwarfs and discussed differences in flower characteristics and cultural requirements that result from different breeding backgrounds.

Bob Sussman is president of the Society for Pacific Coast Native Irises and began the Matilija Nursery in 1992. The nursery sells California native plants and has emphasized Pacific Coast irises for the last ten years. Bob's hybridizing efforts focus on developing irises that are well adapted to the warm climate in Southern California.

Wendy Scott is the president of the Historic Iris Preservation Society (HIPS) and shared information about different preservation programs that help preserve the legacy of iris hybridizers. In this webinar, you can learn more about the HIPS Guardian Gardens program, iris rescues, Breeder Collections, Display Gardens, posterity planning, and the purple-based foliage project.

In my opinion, the only thing better than an iris in bloom is connecting with people who love them just as much as I do. If you have not done so already, consider joining the American Iris Society, one of its specialized sections and cooperating societies, or a local AIS affiliate. You will receive great information from iris growing experts, invitations to programs like these, and opportunities to share the beauty and thrill of the genus Iris.

For Comments:

What iris groups do you participate in?