by Bob Pries

A few nights ago, I was lying in bed while my mind conducted its own internal argument about iris catalogs. One Part of my mind said, “Have you gone nuts! There are 4,600+ catalogs embedded in the Online Library. What good are they?" The Other Part retorted, “But they document the history of irises.”

|

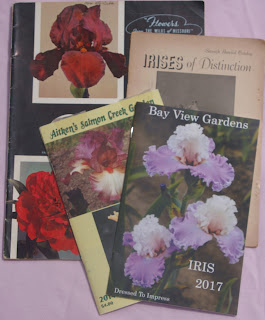

| A collection of iris catalogs |

The first Part replied, “No one cares about history until they are old and see that they are now a part of it. What good does it do now?" And Other Part said, “They can help with identification of older irises surviving today.”

|

| Original description from Goos & Koenemann Catalog, 1909 (p.30) |

|

Photo by Heather Haley |

|

| A different catalog describes this iris as having purple-based foliage |

Part said, “Okay I’ll give you that, but the descriptions they carried were often not much better than the weak historic registration information." Other-Part was now feeling rather sad. Perhaps Part was right and this is an obsessive addiction.

I confess I love to look at all plant catalogs. Even as a 9-year-old I can remember filling out a form in Popular Gardening Magazine that listed about 100 free gardening catalogs. You could check a box and the magazine would forward your name and address to the company. I checked all the boxes and mailed the form. Soon scores of catalogs came to my door and I learned about water gardening, roses, rock gardens, and of course irises. This may have been where I first saw Lloyd Austin’s catalog and his horned irises.

|

An original photograph and description of the"World's First Horned Iris" is part of Lloyd Austin's 1957 Catalog. Photo by Mike Unser |

Austin’s catalog had a contest whereby if you found the 12 typos in his catalog he would send you free irises. I scoured the catalog for days but only found 11. I had my list all planned but never sent the order. At $0.50 a plant, a substantial part of my allowance would be required to meet the minimum order.

Other-Part was now thinking of reasons that a catalog archive could be useful. Each catalog is a record of what is growing in that part of the country (distributors ignored). I could envision a map with counties in green where nurseries were located. This would look like the species distribution maps I have included under USA species on the wiki.

Link to the Biota of North America Program North American Plant Maps

Individual cultivars could be mapped and one could see what hardiness zones a particular clone had thrived in. One could also map by time period, and one could see how iris nurseries moved across the United States, their populations expanding and retreating through time.

Catalogs can also tell us the change in popularity of different classes of irises over time. Just having crudely paid attention I can say definitively that English irises were once very popular and today they can rarely be found. I remember in the late 1800s as many as 150 cultivars were available compared to about 50 tall bearded. Japanese irises seem to have held their own with usually up to 150 varieties available in many years and perhaps still so; but, of course, Japanese irises have been outpaced by TBs today.

The geographic distribution of at least early cultivars may

be interesting if sorted by their species ancestry. I would bet that Iris

aphylla relatives were distributed further North than I. pallida relatives. I

think we sometimes forget that some early irises were not as cold-hardy and

that many tall beardeds which grew well in the South did poorly in the North.

By this time my Parts were getting tired and my brain decided to sleep. I would be interested to hear why you feel it is worth assembling a catalog archive.