by Gary Salathe

Photo: LICI was created in 2020 as a continuation of a program I began within the Greater New Orleans Iris Society.

Charles Perilloux, a member of the Society for Louisiana Irises (SLI), was also invited to give a presentation. Charles is an active member of a group of SLI members that have joined together to preserve unusual forms of species Louisiana irises that have been collected from the wild. Their efforts are completed as part of the Louisiana Iris Species Preservation Project. His presentation also included a description of what his group is doing and why.

Charles and I were each given 20 minutes to present, followed by a 20-minute question and answer session. Hopefully, we accomplished their goals for inviting us to do our presentations.

AIS Region 2 is comprised of three iris societies in the state of New York and the Ontario Iris Society, whose members are from the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec. The invitation for us to give our presentations was due to the Region 2 AIS members being interested in learning about efforts underway in other parts of the country to preserve or restore wild native species irises. One reason for this interest was to better understand how these activities bring in younger volunteers and others that want to be involved in environmental issues and habitat restoration.

This photo from my presentation was used to illustrate how wild Louisiana irises are not only taken for granted by many landowners in south Louisiana; but since they are not a protected species, they are seen as expendable by landowners if their property is to be developed. This site, west of New Orleans and privately owned and undeveloped, has attracted visitors from the Greater New Orleans Iris Society for years during the iris bloom. (Yes, you are correct. The photo is of irises being bulldozed and covered with fill at the site AS THEY ARE BLOOMING.)

The Louisiana Iris Conservation Initiative volunteers “rescue” irises that are threatened with destruction after we get permission from the landowner to remove them. If the rescue events take place during the summer or early fall, we replant the irises in containers at our iris holding area to allow them to strengthen up as they start their winter growth period in September. Starting in late October we begin organizing iris planting events where the irises are planted at area refuges and nature preserves. We also hold iris rescue events during the winter where we rescue irises from sites and then replant them in protected locations within a few days.

The LICI iris holding area is in the Lower Ninth Ward neighborhood of New Orleans. The goal each year is to have all of the containers empty by the end of January. LICI does not propagate irises.

We have also started a program where we plant the rescued irises, if enough are available, in area parks where they can be seen by the public while they are blooming. The purpose of this program is twofold; to educate the public about this special native plant and to have the irises increase in numbers. We have an agreement with these locations that allow us to come back in the future to thin the irises out for use in our other projects. We intend to use this option if we do not have any iris rescue sites available when a need comes up.

Volunteers, including the town mayor, at LICI’s Louisiana iris planting done in partnership with a local restoration group at City Park in New Iberia, Louisiana. The volunteers planted 425 I giganticaerulea species of the Louisiana iris from LICI’s iris rescue program on October 1, 2022.

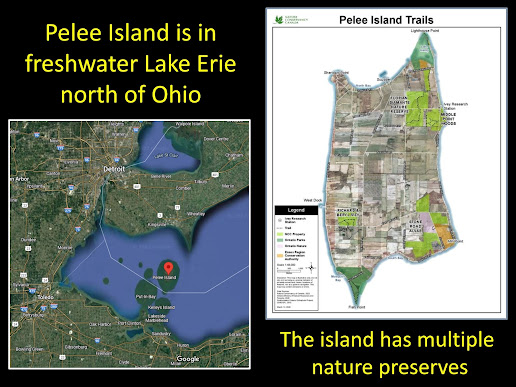

AIS Region 2 Regional Vice President Neil Houghton, who invited Charles and me to give presentations, was interested in whether or not any of our activities could be replicated in their area. I set out on the internet to learn if this was possible and my search quickly found a blog post from 2015 where iris aficionados discussed the possibility of irises still surviving on Pelee Island in the Canadian province of Ontario. The iris in question was the I. brevicaulis, a species of Louisiana iris. Ontario province is the extreme northern border of the I. brevicaulis’ range.

Continuing my internet search with this new information, I learned that Pelee Island is located in Lake Erie between the Canadian mainland and the US state of Ohio. Apparently, it is home to many species of birds, plants, and wildlife that are not found anywhere else in Canada because it is the southern-most part of Canada and the waters of Lake Erie temper its climate.

I found numerous references to

a local botanist on Pelee Island in articles about the native habitats and

restoration work being done there. I was

able to locate a local nature group’s Facebook page; and by sending them a

message through the page, they were good enough to let me know how to contact the botanist. The botanist and I exchanged emails and later talked by phone. I discovered that he was concerned about the I. bevicaulis’ long-term

survivability on the island and had collected some specimens and was growing

them on his farm in an attempt to preserve them and increase their numbers. He was not aware that this iris is a species of the Louisiana iris.

An example of the work being done by The Nature Conservancy on Pelee Island to convert farmland back into native habitat.

The botanist then directed me to The Nature Conservancy’s Coordinator for Conservation Biology for the Conservancy’s properties on Pelee Island. It turns out that the organization has a long-term project underway on the island to purchase farmland and convert it back into native habitat. They currently own 10% of the land on the island under this program. Obviously, there is a need for native plants to replant this land once the conversion takes place.

After satisfying my curiosity that the work being done on Pelee Island might offer iris societies opportunities for involvement, I continued my internet search, looking for other possibilities in New York state or the New England states. I selected two iris species that are native to these areas to see what opportunities may exist for them: the Slender Blue Flag (Iris prismatica) and the Northern Blue Flag (Iris versicolor).

Using the same methods I employed to locate people on Pelee Island I was able to email and follow-up with phone calls to two key people that helped me understand not only the status of these irises, but also if and how people could become involved in their restoration.

I learned from the Senior Ecologist and Botanist for the State of New Hampshire that they take the lead on the restoration of plants and habitats from observations and recommendations supplied to them by the Native Pant Trust.

The Native Plant Trust was founded over 100 years ago to stop the destruction of native plants in the New England states. They have now expanded that mission to locating, mapping, and documenting the habitats of all land in these states. They send out volunteers each year to monitor important native habitat, including inspecting and counting threatened plants.

The Native Plant Trust then sends a report with recommendations to each state's biologist or botanist if they find any species of plants that are in decline or threatened. Each state can then take that information and make a decision on what should be done and then the state implements a plan of action.

I can sum up what I learned from talking to these two individuals with this: In the New England states, although it varies from state to state or even county to county, anything done involving native plants is tightly controlled. I was told that in one area to dig native plants, including irises, from one part of your private property to replant them on another part of your property requires a permit that involves a detailed review of your plans by local officials. (I didn’t have the heart to send them the above picture of the Louisiana landowner bulldozing native irises as they are blooming.)

The Native Plant Trust

has a huge need for volunteers. They will

train each person for the task the individual wants to do. They have a nursery where they grow and sell native plants. (I did not have time to discover if they are growing the

Northern Blue Flag iris species in their nursery for people to plant

into their gardens.) They also organize invasive plant species removal, have a wild seed collection and seed bank program, and have

over 500 volunteers that go out to do the inspections of native habitats and update the status of the native plants found there. I was told they need more site monitor volunteers to do the inspections.

I believe there are plenty opportunities for local iris societies to get involved in native iris species restoration and preservation. I had the same feeling talking to the two individuals as I did when I first talked to the local managers of refuges near me, that the irises are not really that much on their radar screens. The irises seem pretty low on their priority list because there are so many other pressing issues they are dealing with. Local iris societies helping to raise awareness of the native species of irises and their threatened status could help move the iris up on the priority list of the people making the decisions. Offering to volunteer to focus on doing iris counts out in the wild may be another way to help with this effort.

|

| Range of the Northern Blue Flag |

I was told that the Slender Blue Flag iris is so rare in the wild that any group wanting to work on its preservation will need to work with a governmental agency. However, the Northern Blue Flag iris’ situation is very similar to the I. giganticaerulea native iris that my group works with. It’s threatened in many areas, extinct in a few areas, and can be found in abundance in some areas. It could be an iris where, if someone has the fortitude to wade through the permit process, LICI's programs could be replicated by putting native irises in locations where they can be viewed by the public as an educational tool while the irises are also growing and increasing in numbers.

Its important to keep in mind that the investigation I did for my presentation was limited. I randomly picked two geographical areas in or near AIS Region 2 to see what I could learn quickly. However, there must be an unbelievable number of refuges, nature preserves and parks throughout the United States within the ranges of other wild native irises that offer many possibilities for other iris societies to get involved.

Its true that the northeastern states’ tightly controlled environmental policies may make it impossible for an iris society to go out on its own and launch iris restoration projects as LICI has done in southeastern Louisiana. However, it's important to keep in mind that we, too, have had to apply for permits in many of the sites where we work. It’s not always an insurmountable problem and the solution has a lot to do with how the local refuge or park manager judges the importance of your proposed iris project in meeting their goals. We've learned that if you are helping them, they are willing to help you. Conversely, you will likely discover that you don't get much encouragement from them if you are adding to their workload.

Charles’ presentation also offered the possibility of iris societies helping the iris preservation cause by growing out plants from either rhizomes or seeds to supply to others for planting. Like the botanist on Pelee Island, one iris person growing out 100 native irises for the refuge down the road from where he or she lives could have a huge impact if no one else is doing it.

My last thought on all of this is something that came up while I was surfing the internet to prepare for my presentation: The national and international effort to create native plant gardens and protect native plants is growing exponentially. I can’t begin to tell you how many native plant groups my internet searches directed me to. There is no question that as traditional garden clubs are struggling to keep and attract members, the native plant organizations are expanding and growing in substantial ways. (Many of the people I spoke with on Pelee Island wanted to tell me all about the island's Butterfly Sanctuary. I had to work hard to keep them on track talking about irises!)

It's possible that having some aspect of native irises become a part of this movement may be very important to the long-term future of iris organizations. I'm sure its not a coincidence that both the Greater New Orleans Iris Society and AIS Region 2's Greater Rochester Iris Society had guest speakers on native plant gardens at their recent general membership meetings.

I really appreciate the AIS Region 2 inviting me to give the presentation, and I hope they found it informative and useful. I also appreciate the donation they made to LICI!

The LICI Facebook page can be found here.

You can email Gary Salathe at: licisaveirises@gmail.com

Although LICI “is a bare-bones deal”, as Gary likes to say, he is quick to add that they can always use donations to their cause. They have a “Donate” button at the top of their website home page here.

.jpg)